Civil Rights / Cold War

School Desegregation

Schools in Tennessee were segregated during most of the 1900s. This meant that whites went to different schools than blacks.

Under Jim Crow laws , these schools were supposed to be “separate-but-equal.” In reality, public schools for blacks were vastly inferior.

Under Jim Crow laws , these schools were supposed to be “separate-but-equal.” In reality, public schools for blacks were vastly inferior.

The main group to push for desegregation was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In 1954, the Supreme Court issued the ruling in Brown v. Board of Education that schools should be desegregated with “all deliberate speed.”

Even though it sounded like the change would be quick, it took years for southern states, including Tennessee, to fully integrate. Although the desegregation of Clinton High School in 1957 attracted national media attention, school integration still had to be battled for in individual school districts throughout Tennessee.

Even though it sounded like the change would be quick, it took years for southern states, including Tennessee, to fully integrate. Although the desegregation of Clinton High School in 1957 attracted national media attention, school integration still had to be battled for in individual school districts throughout Tennessee.

In Nashville, the father of a black student, Bobby Kelley, sued the school board to allow his son to attend nearby East High School instead of being bused across town to the all-black Pearl High School. He was represented by black attorneys Avon Williams, Jr. and Z. Alexander Looby. When the lawsuit was heard in 1957, the federal judge ordered the board to come up with a desegregation plan.

School administrators designed a plan to desegregate one grade at a time beginning with first graders. The board then redrew the school districts to try and keep all white school districts serving mostly white families.

Out of 1,400 black first graders in Nashville that year, only 115 lived in an all-white school district. After they gave African American parents the option of transferring to an all-black school, only 19 black first graders went to a previously all-white elementary school. Dig Deeper: How hard was it for African American parents to send their first graders to all white schools?

Out of 1,400 black first graders in Nashville that year, only 115 lived in an all-white school district. After they gave African American parents the option of transferring to an all-black school, only 19 black first graders went to a previously all-white elementary school. Dig Deeper: How hard was it for African American parents to send their first graders to all white schools?

The mood in Nashville was tense at the beginning of the school year. The police chief announced that anyone who attempted to interfere with desegregation would be arrested.

But the scene worsened when John Kasper, a racist agitator who had inflamed protesters at Clinton the year before, arrived in Nashville to do the same. He spoke at several meetings calling for resistance to school desegregation.

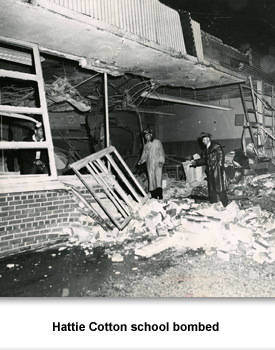

Police officers kept a watch on Kasper, and when Hattie Cotton School was bombed, they picked him up even though there was no evidence he was involved. He was charged with disorderly conduct. As soon as he posted bail, police re-arrested him on another charge--one of the charges was parking in a restricted zone. It was obvious that Nashville police were not going to allow him out of jail.

But the scene worsened when John Kasper, a racist agitator who had inflamed protesters at Clinton the year before, arrived in Nashville to do the same. He spoke at several meetings calling for resistance to school desegregation.

Police officers kept a watch on Kasper, and when Hattie Cotton School was bombed, they picked him up even though there was no evidence he was involved. He was charged with disorderly conduct. As soon as he posted bail, police re-arrested him on another charge--one of the charges was parking in a restricted zone. It was obvious that Nashville police were not going to allow him out of jail.

On the first day of school on September 9, 1957, hundreds of white protesters stood outside of the schools with signs shouted at the students and their parents. For one African American student the crowds weren’t frightening. She had never been to school before and thought that “everyone went to school with a parade.”

The next day a bomb destroyed an entire wing of the Hattie Cotton Elementary School in Nashville. It exploded after midnight so no one was injured. No one was ever arrested for the crime. The number of African American children attending a formerly all-white school dropped to 11 after the Hattie Cotton bombing.

Despite the dangers, the NAACP registered a number of legal victories in Tennessee, where Davidson County, Knoxville, and Memphis public schools, and Memphis State University and the University of Tennessee were all forced to desegregate during the 1950s.

By 1964, a new Civil Rights Act was introduced into Congress outlawing discrimination in voting, public accommodations and facilities, education, and employment. In 1965, Viola McFerren filed a lawsuit seeking to allow her son to attend all white schools in Fayette County. A year later the court ruled in her favor.

Federal courts were not impressed by school districts drawn around white neighborhoods. Under court order in 1971, public schools in Tennessee began busing black and white students to schools that were once divided by race.

Unexpectedly, many new private schools were created for white children whose parents did not want their children bused. In the ten years after busing began in Davidson County, private schools doubled their enrollment. This “white flight” often left newly integrated public schools for all purposes segregated again.

Unexpectedly, many new private schools were created for white children whose parents did not want their children bused. In the ten years after busing began in Davidson County, private schools doubled their enrollment. This “white flight” often left newly integrated public schools for all purposes segregated again.

Picture Credits:

- Photograph of Linda Gail McKinley’s first day at Fehr Elementary School on September 9, 1957. McKinley (second girl from left) walks with her mother past whites protesting racial integration. Note the white children in the photograph. Many white parents kept their children out of school on the first day. Nashville Banner Archives, Special Collections Division, Nashville Public Library

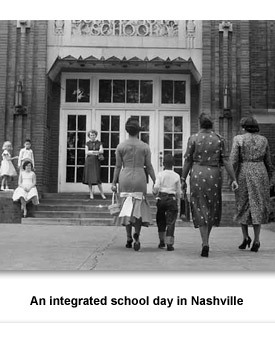

- Photograph of an integrated school day in Nashville. Three African American women walk a boy into Buena Vista elementary school on September 9,1957. It was the first day of integrated classes. The Nashville plan was to integrate one grade per year staring with first grade. At that rate it would take years to achieve desegregation. Photo by Jimmy Ellis, courtesy of The Tennessean

- Photograph of Nashville’s Hattie Cotton School after it was bombed on September 10, 1957. Mayor Ben West (center) looks over the wreckage. Nashville Banner Archives, Special Collections Division, Nashville Public Library

-

Police officers walk through debris after Hattie Cotton Elementary school was bombed in the early hours of September 10, 1957. No one was hurt in the bombing since the school was empty. The bombing was apparently in response to the integration of Nashville public schools on September 9. Photo by Bill Preston, courtesy of The Tennessean

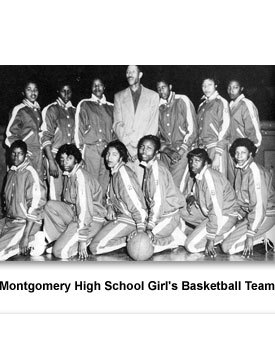

- Photograph of the Montgomery High School Girl's Basketball Team. This photo was taken in 1953 in Lexington, Tennessee. It shows an African American girls basketball team posing for a group photo along with their coach. Published in the 2005 Henderson County, Tennessee Connections: A Pictorial History by Brenda Kirk Fiddler,

Civil Rights / Cold War >> Civil Rights Movement >> Winds of Change >> School Desegregation

Sponsored by: National Endowment for the Humanities

Sponsored by: National Endowment for the Humanities