Child Labor

As industries grew, the demand for workers grew also. Children, who had previously worked at home and on farms, were drawn into the work force at factories and other industries.

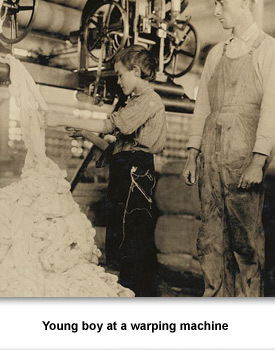

The main reason for this was money. Wages for factory workers were so low that families needed the extra income provided by children. Business owners liked to hire children for unskilled jobs because they could pay them less. For example, in 1911 in Fayetteville, Tennessee, Leo, an eight year old boy, earned 15 cents a day working in the Elk Cotton Mills.

The number of children under 15 years old who were working in the United States in 1910 was estimated at 2 million. Some of these children began to develop health problems. They were underweight and often sick.

Many Americans were horrified about child labor and the conditions these children worked under. In 1904 a group of reformers founded the National Child Labor Committee. Its goal was to abolish child labor. It hired people to gather information about children working in factories and then organized photographic exhibits to show congressmen. Read about Lewis Hine’s photographs of working children.

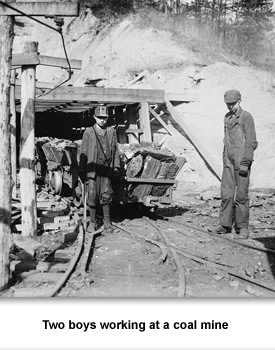

Meetings were held by the Southern Sociological Congress in Nashville to discuss a number of progressive topics, including decreasing child labor and the compulsory school attendance. Child labor was common in Tennessee. Many textile and coal mills in the state employed young children.

In 1881, the state passed a law prohibiting children under twelve from working in mines. (In 1902, 14-year-old Elbert Vowell died in the Fraterville Mine disaster.) In 1893 the law was revised to include child employment in workshops, factories and mills. However, by 1908 children could still work 60 hours a week in other jobs. Many employers ignored the law. They often claimed the younger children were at the factories “helping” their mothers or sisters.

By 1920, children in Tennessee no longer worked in dangerous occupations such as mining. But some children still worked long hours for small employers. This is because there was an exemption so people could hire children for agricultural or domestic employment.

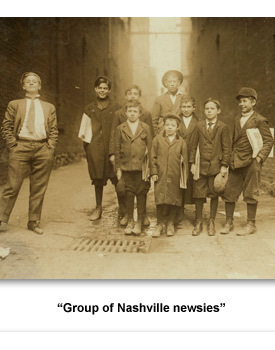

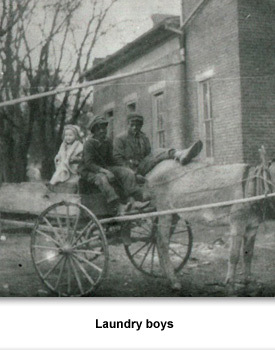

In larger cities such as Nashville, downtown streets were filled with newspaper boys as young as six years old. Rising as early as five in the morning, they could work as late as 11 p.m., and regularly missed school. In Knoxville 94 percent of African American boys age ten to twenty years old were employed, mostly as caddies, shoe shiners, porters, or delivery boys.

Major reform efforts on child labor weren’t passed until the New Deal in the 1930s. But the efforts of these early reformers had cut the number of working children in half by the 1920s.

Picture Credits:

- Photograph showing Little Fannie, age seven, helping her sister work. This photo was taken by Lewis Hine in Fayetteville, Tennessee in November 1910. Both girls work at the Elks Mills and belong to a family of 19 children. Her sister said, “Yes, she he’ps me right smart. Not all day but all she can. Yes she started with me at six this morning.” Library of Congress.

- Photograph of two boys working at a coal mine. This photo of was taken by Lewis Hine in Coal Creek, Tennessee in December 1910. One of the boys is James O’Dell, who had been working for the Cross Mountain Mine, Knoxville Iron Company for four months. He is about 12 or 13 and helps push the heavily loaded cars. Library of Congress.

- Photograph of Leo working at the Elk Cotton Mills. This photo was taken by Lewis Hine in Fayetteville, Tennessee in November 1910. It shows Leo, whose job it was to pick up bobbins at 15 cents an hour, at eight years old. He is not wearing shoes. Leo said, “No, I don’t help my sister or mother, just myself.” Library of Congress.

- Photograph of a young boy at a warping machine at the Elks Cotton Mills. A warping machine helps prepare yarn to be made into cloth. This photo was taken by Lewis Hine in Fayetteville, Tennessee in November 1910. Library of Congress.

- Photograph showing a little girl standing on a box. This photo was taken by Lewis Hine in December 1910 in Loudon, Tennessee. The girl must stand on a box in order to reach her machine and perform her job as a knitter at the Loudon Hosiery Mills. She said she did not know how long she had been working at the mill. Library of Congress.

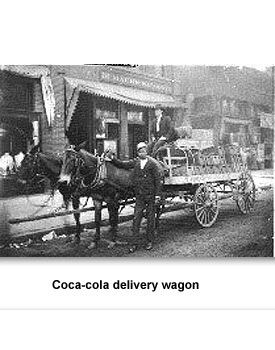

- Photograph of a Coca-cola wagon. This photograph was taken in 1905 in Memphis. The driver is Landan Smith. An African American boy, possibly an assistant, is also shown posed beside the wagon. Tennessee State Library and Archives.

- Photograph of Harley Bruce, a young mine coupler at the Indian Mountain Line of Proctor Coal Co. A coupler helped to haul the mine carts. This photo was taken by Lewis Hine in December 1910 near Jellico, Tennessee. It shows Bruce, who had been working at the mine for a year, at about 12 or 14 years old. The caption says that the work is, “…hard and dangerous. Not many young boys employed in or about the mines in this region.” Library of Congress.

- Photograph entitled, “Group of Nashville newsies.” This photo was taken in November 1910 in Nashville. In the middle of the group is Sam, who is 7 years old. The caption reads, “Smart and profane. He sells nights also.” Library of Congress.

-

Photograph showing two laundry boys. This photo was taken in 1905 in Wilson County, Tennessee. It shows two African American boys driving a horse and wagon in front of the Divinity Hall at Cumberland University. A young girl, Marge Margaret Bevan, is also shown riding in the back of the wagon. Tennessee State Library and Archives.

Confronting the Modern Era >> Life in Tennessee >> How They Worked >> Child Labor

Sponsored by: National Endowment for the Humanities

Sponsored by: National Endowment for the Humanities