Civil Rights / Cold War

G.I. Bill of Rights

The G.I. Bill of Rights, the popular name for the Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, caused dramatic changes to people’s lives after World War II.

This act provided federal benefits in education and housing to 7.8 million veterans across the nation.

This act provided federal benefits in education and housing to 7.8 million veterans across the nation.

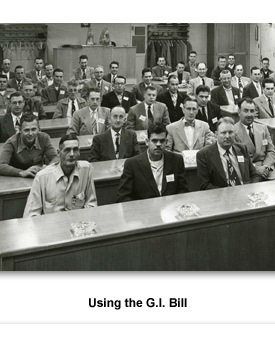

One of the most important benefits was the educational one. Veterans who served at least 90 days received financial help to attend college or vocational school.

Not everyone wanted to go to college. Many more veterans received vocational training classes for jobs in air conditioning, welding, plumbing, and heating. This contributed to the technological advancement of the United States. Employers encouraged their workers to take classes using the G.I. Bill.

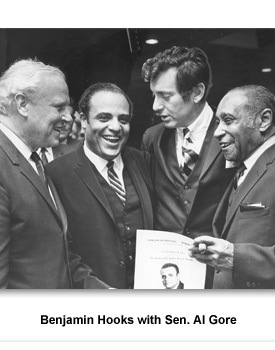

White and black veterans flocked to colleges and universities like Memphis State and Lemoyne College. Benjamin Hooks was one African American who took advantage of this plan to complete his law degree.

Historically black colleges had sharp increases in attendance and received federal funds for new school buildings. Many black veterans who could not get into overcrowded black colleges were still unable to attend all white universities. This would begin to change in the 1960s with the Civil Rights Movement.

In 1939 there were 1.5 million enrolled in colleges and universities. By 1949 this figure had jumped to 2.6 million. Most of this increase was due to the G.I. Bill.

This easier access to college education encouraged parents to later send their children to college. By 1969, when children of WWII veterans were going to college, total national enrollment was 8 million.

This easier access to college education encouraged parents to later send their children to college. By 1969, when children of WWII veterans were going to college, total national enrollment was 8 million.

Access to education was part of the reason that people in the U.S. started living more affluent lives. Whether their education was from a college or vocational school, it enabled them to get better paying jobs.

Picture Credits:

- Photograph of a mechanical engineering class held in Nashville in 1948 in a now closed school. Many of the men attending the class did so using the G.I. Bill. Tennessee State Museum Collection

-

A photograph of Benjamin Hooks (second from left) standing between Sen. Al Gore (l) and Nashville lawyer John Jay Hooker, Jr., with George Lee at the far right. Hooks used the G. I. Bill to attend Depaul University in Chicago. He became a successful lawyer and was appointed the first African American judge in Tennessee since Reconstruction by Governor Frank Clement in 1965. Courtesy of University of Memphis Special Collections

- Photograph of LeMoyne Owen College in 2007. Historic black colleges and universities like LeMoyne in Memphis benefited from the G. I. Bill as African American veterans swelled their student enrollment. Photo by G. Graham Perry III, Tennessee State Museum Collection

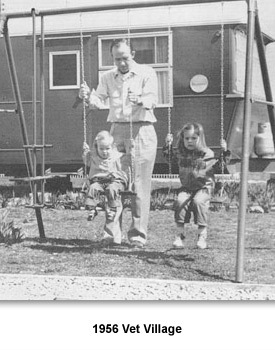

- Middle Tennessee State College established a "Vet Village" with trailers for veterans to live in while attending college there on the G.I. Bill. Here, in 1956, Raymond Nunley, a veteran of World War II and the Korean War, swings his daughters at the village. Albert Gore Research Center, Middle Tennessee State University

Civil Rights / Cold War >> Everyday Life >> How They Worked >> G.I. Bill of Rights

Sponsored by: National Endowment for the Humanities

Sponsored by: National Endowment for the Humanities