Fighting Disease

The growth of Tennessee cities caused health problems. People lived in small houses or apartments without running water or basic sanitation. Outhouses were common, even in cities, with sewage polluting streams and rivers.

Diseases such as diphtheria, diarrhea, smallpox, measles, scarlet fever, typhoid, and malaria were problems in urban areas.

In the 1870s Nashville city officials started a Department of Health to inspect homes, water wells, as well as meat and milk suppliers.

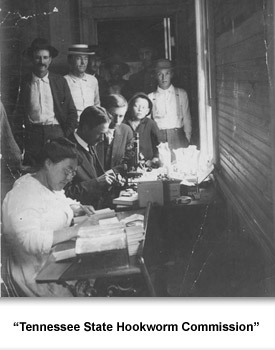

Hookworm infestation was widespread in the South and Tennessee. Hookworms can infect human intestines causing serious health problems. Hookworms are found in soil that is contaminated with fecal material. The worms enter the body by penetrating the skin, usually through bare feet.

The Rockefeller Sanitary Commission (RSC) led a campaign to educate people about hookworms. RSC set up 39 county treatment centers in Tennessee offering diagnosis and treatment.

Yellow Fever epidemic

Memphis began many public health reforms in this time. These reforms were spurred by deadly yellow fever outbreaks in the 1870s. The numerous deaths from the disease helped push the movement for better sanitation and public services in the city.

Yellow fever is a terrible disease. Victims’ skin and the whites of their eyes turn yellow, thus giving the disease its name. There is internal bleeding which comes out through the eyes, nose, and ears. One of the symptoms is “black vomit” which comes from bleeding in the stomach.

Memphis, located on the banks of the Mississippi River, had several outbreaks of yellow fever which is spread from person to person by mosquitoes. But none of the outbreaks could compare to the one in 1878.

There had been an outbreak of the disease in New Orleans in the summer of 1878. The mayor of Memphis imposed a quarantine on people entering Memphis, but he allowed shipments of goods by river and rail to enter the city. On August 14, 1878, a woman who ran a snack shop near the riverfront died. It was the first of many deaths.

The news of the death set off a panic among the residents. It is estimated that some 27,000 people fled the city, leaving behind 19,000.

“On any road leading from Memphis, could be seen a procession of wagons, piled high with beds, trunks, and small furniture…carrying women and children. Besides these walked groups of men, some riotous with excitement, others moody and silent from anxiety and dread,” wrote one of the St. Mary’s Episcopal nuns who stayed in the city.

Of the 19,000 people left in the city, many of them poor, 17,000 would get sick. More than 5,000 people died. It is estimated that in the entire Mississippi Valley more than 20,000 people died.

Some people remained in the city to help tend the sick. The nuns at St. Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral stayed, and were often called to homes to help. Six nuns and priests became ill and died from the disease. They are now considered saints by the Episcopal Church. Read excerpts from letters from the nuns and people who worked with them.

Memphis Improvements

The costs of the epidemic bankrupted the city of Memphis causing the state to revoke its city charter. When the city charter was restored, city officials, determined to stop future outbreaks, constructed more than 45 miles of new sewers. The city also made water a public utility by purchasing the Artesian Water Company in 1903.

In 1909 the Board of Commissions created departments for sanitation, chemistry, bacteriology, contagious diseases, and school and dairy inspection in efforts to improve the general health of the city. However, as late as 1915 diseases like pellagra and tuberculosis continued to cause many deaths, especially among children in the city.

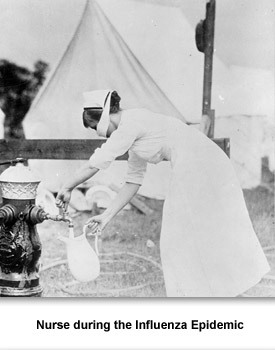

Influenza Pandemic

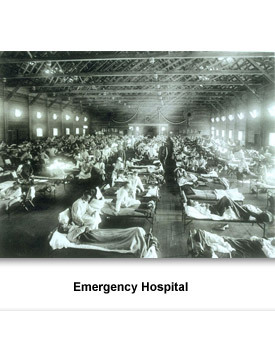

No one is sure where or how the 1918 Influenza (flu) -pandemic- began. The earliest records point to a town in Kansas where it rapidly spread to the nearby Fort Riley Army Base. This was during World War I, so the soldiers from Fort Riley were shipped to the east coast and then to Europe, carrying the flu germs with them. From there it spread around the world.

Eventually the flu would kill 600,000 Americans. No one knows how many people died worldwide. Some estimates are that as many as 50 million people died. Unlike most flu outbreaks that kill the old and the very young, this one killed adults in the prime of their life.

Public health officials understood that the flu germ could be passed from person to person. And since healthy-looking people can still be carrying the germs and infecting others, doctors tried to convince government officials to isolate areas that were infected. But often this did not work. Even after doctors told the army to stop transferring men between infected and uninfected camps, they continued to do so.

Around the first of September, 1918, a train with 3,108 healthy-looking soldiers left from Camp Grant, an infected camp in Pennsylvania, for an uninfected camp in Georgia. By the time the train got to Georgia, 700 men were sick, eventually 2,000 men on that train became ill. The disease was now in the South.

On September 27, the state of Tennessee reported to the Public Health Service that there were two suspicious cases in Memphis. By October 1, there were 95 flu cases in Memphis, and 76 deaths related to the flu in Nashville. This means the disease was probably in Nashville before September 27.

Although records were not kept, one historian has estimated that 40,000 people fell ill in Nashville. City and county schools were closed October 8. Ministers were told to close their churches while nonessential businesses were closed.

One of the hardest hit areas was Old Hickory, a small area in Davidson County. A large powder plant had been built there to produce material for the war effort. Workers lived nearby in overcrowded conditions. By October 17, more than 400 workers were hospitalized. It is estimated that 465 people died from the flu in Old Hickory. Schools reopened November 1st indicating that the situation had improved.

Safer & Healthier Foods

At the beginning of the 1900s, people kept food fresh by placing it on a block of ice, in a spring house (a small shed built over a spring in the ground), burying it in the yard, or storing it on a window sill outside during cool weather. Even then, sometimes the food got too warm, growing bacteria which caused people to get sick and even die.

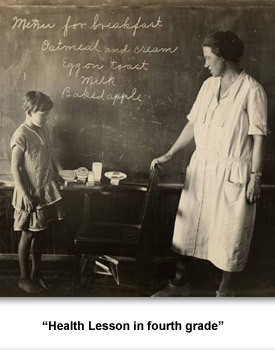

During the 1920s, electric refrigerators became available for household use. Pasteurization, invented by Louis Pasteur, became widely used in milk production. By 1916, scientists had dis-cover-ed that food contained vitamins and that people needed to get vitamins in order to remain healthy. The next year the U.S. Development Agency issued the first diet recommendations about the five food groups. In 1924, iodine was first added to salt to prevent goiter, a disease of the thyroid gland.

For more information about the 1918 flu pandemic, click here.

Picture Credits:

- Photograph showing immunizations being given by a nurse to a woman and child. This photo was taken in Gatlinburg, Tennessee in 1922. Pi Beta Phi to Arrowmont Photographic Collection, University of Tennessee.

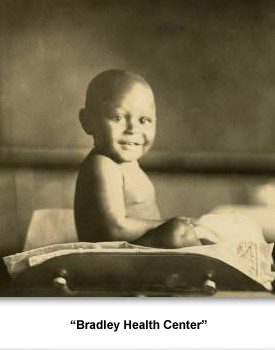

- Photograph entitled, “Bradley Health Center” in Rutherford County, Tennessee. The photo shows a smiling African American baby sitting in an infant weight scale. It was taken sometime between 1924 and 1928 by Dr. Harry Mustard. Tennessee State Library and Archives.

- Photograph showing a nurse during the Influenza Epidemic. The nurse is wearing the mask in order to protect her from the disease. This photo was taken on September 13, 1918. National Archives and Records Administration.

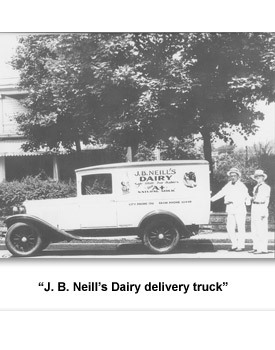

- Photograph entitled, “J. B. Neill’s Dairy Delivery Truck.” This photo was taken in 1925 and shows two workers, Sonny Neill and Stella Moser standing beside a milk truck. The design on the truck features a picture of a cow and a woman holding a baby inside a milk jar. The slogan on the truck reads, “Safe Milk for Babies” and “Grade A+ Natural Milk.” Hamblen County Archives.

- Photograph entitled, “Preparations for Waste Disposal Eagleville School.” The photo shows three men laying a sewer line. It was taken by Dr. Harry Mustard sometime between 1924 and 1928 in Eagleville, Tennessee. Tennessee Library and Archives.

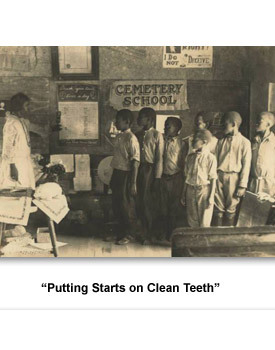

- Photograph entitled, “Putting Stars on Clean Teeth Chart.” The photo shows an African American school where a teacher is instructing a group of young boys about brushing their teeth. The caption states, “Health Lesson Cemetery School.” This photo was taken by Dr. Harry Mustard sometime between 1924 and 1928 in Rutherford County, Tennessee. Tennessee State Library and Archives.

- Photograph entitled, “Health Lesson in fourth grade.” The picture depicts a teacher instructing a young girl about a healthy breakfast. The writing on the blackboard reads, “Menu for breakfast, Oatmeal and cream, Egg on toast, Milk, Baked Apple.” This photo was taken by Dr. Harry Mustard sometime between 1924 and 1928 in Rutherford County, Tennessee. Tennessee State Library and Archives.

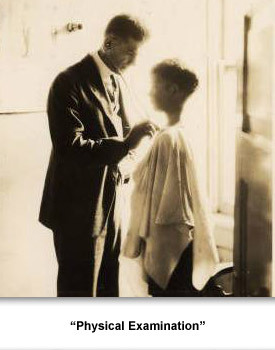

- Photograph entitled, “School Examinations.” The photo shows a doctor giving a medical examination to a young boy. This photo was taken by Dr. Harry Mustard sometime between 1924 and 1928 in Rutherford County, Tennessee. Tennessee State Library and Archives.

- Photograph showing an emergency hospital set up at Camp Funston, Kansas during the Influenza Epidemic of 1918. National Museum of Health and Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology.

- Photograph entitled, “Tennessee State Hookworm Commission.” This photo was taken in 1915 in Gatlinburg, Tennessee. It shows Dr. Yancey of the Tennessee State Hookworm Commission working with his assistant, Mary Pollard, and others in a mountain community. Pi Beta Phi to Arrowmount Photographic Collection, University of Tennessee.

- The Old Hickory Powder Plant, located in Old Hickory, north of Nashville, was hit hard during the influenza pandemic. At one point nearly 400 workers were hospitalized. Courtesy of the Old Hickory Area Chamber of Commerce

Confronting the Modern Era >> Life in Tennessee >> Making Life Better >> Fighting Disease

Sponsored by: National Endowment for the Humanities

Sponsored by: National Endowment for the Humanities