Lynching

Lynching is the unlawful killing of a person, usually by hanging.

Sometimes the victim was tortured—beaten or mutilated—before he was hanged. Some victims’ bodies were burnt before or after they were hanged. The lynching might be done by a few or there might be a large group of people. It was a very violent act.

Before the Civil War, many lynching victims were white. After the Civil War and into Reconstruction, however, most mob violence in both the North and South was directed at African Americans.

Records are not exact, but it is estimated that 2,462 African Americans were killed by mobs. In Tennessee there were 214 victims between 1882 and 1930. Of this number 37 were white, 177 were black and the rest are unknown.

While most victims were men, there were women who were lynched. In 1886 a black woman, Eliza Wood, who had been accused of poisoning a white woman, was removed from the jail in Jackson and hung.

In 1911, a Clifton farmer, Ben Pettigrew, was shot and his two daughters hung by four white men. Two of the attackers were later convicted in court and hung by the authorities for their crime.

Lynchings were often treated as normal occasions by newspapers. In Memphis, where the largest number of lynchings occurred (18), newspapers sometimes announced in advance the place and time for a lynching.

Other newspapers tried to absolve their community of the actions. For example, Chattanooga newspapers in 1906, after Ed Johnson was lynched, condemned the mob for taking the law into its own hands. But the newspaper editor placed the responsibility on the defendant’s appeal to federal courts that “revived the mob’s spirit and resulted in the lynching.”

Although some Tennesseans accepted lynching as a necessary evil, others did not. In 1931, a group of white men stormed the Carroll County jail intent on lynching a black prisoner. The sheriff’s wife, Mrs. J.R. Butler, met the men and told them her husband wasn’t there. She then told them they weren’t taking the prisoner, saying “You couldn’t run anything like that over me.” They turned around and left.

In 1915 in Deaden, Tennessee, a mob took a black man and put a noose around his neck for an alleged crime, but let the man go when the victim’s husband said he didn’t want anyone killed. In fact, it is estimated that more than half of attempted lynchings failed, usually because the law officials moved the prisoner or protected him.

Local African Americans were intimidated by lynchings. The threat was if they tried to intervene, then they also could be attacked. Still some protested the practice. In 1918 more 2,000 African Americans marched in protest of a lynching in Estill Springs, although the white press did not widely -cover- the march.

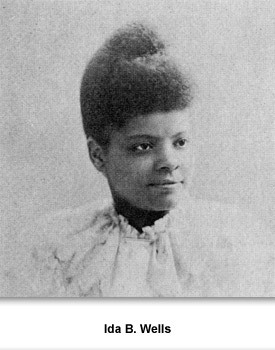

Other African Americans also attempted to protest segregation and violence against their race. Ida B. Wells wrote articles in local black newspapers in Memphis condemning lynchings. There were so many threats made against her life that she had to leave Memphis and move north.

To read more about Ida B. Wells, click here.

Public sentiment gradually began to turn against mob violence and the lynchings that were often associated with it.

Northern newspapers regularly reported the most atrocious episodes and condemned the participants. “The mobs that kill Negroes and the communities that excuse the killers, are barbarous. The men engaged in the bloody work in Tennessee and Alabama are murderers, and should be hanged.”

Ultimately, both blacks and whites began to work toward ending the practice of lynching in Tennessee. The last person lynched in Tennessee is thought to have been Elbert Williams of Haywood County, who died in June 1940. He had attempted to register to vote, and also established a NAACP chapter in the county.

Picture Credits:

- Photograph of Ida B. Wells. This photo was published in 1897 and included in the work Sparkling Gems of Race Knowledge Worth Reading by James T. Haley. It shows Wells in her mid thirties. Project Gutenberg Archives.

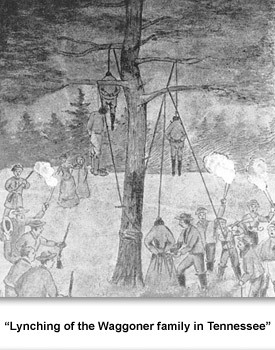

- A print entitled, “Lynching of the Waggoner family in Tennessee.” This lynching of the Waggoner family included the father, son, son in law and daughter and occurred in 1893. The caption suggests that no one in the family was accused of a crime. This print was published in 1897 in the work The Tragedy of the Negro in America by Thomas P. Stanford. New York Public Library.

Confronting the Modern Era >> Racial Segregation >> Jim Crow Laws >> Lynching

Sponsored by: National Endowment for the Humanities

Sponsored by: National Endowment for the Humanities