Leaving

Robert Church of Memphis sent his young daughter Mary to live with relatives in Ohio and go to school there.

Ida B. Wells left Memphis because of threats to her safety from whites who disliked her newspaper articles about mistreatment of blacks.

Others left the South to make a living elsewhere. In 1910, 80 percent of all U.S. African American citizens lived in the South. By 1970 less than one-half lived in the South.

The two major causes were the hardships in the South, both economic and racial, and the pull of opportunities in the North.

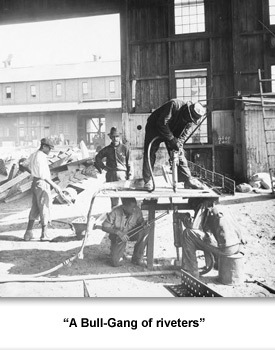

World War I and laws restricting immigration had caused a shortage of workers at northern factories. Northern companies even sent recruiters to the South to try to get workers to move north. For skilled black workers, industrial jobs that drew them to the North did not exist in Tennessee for them—they were for white workers only.

African American newspapers promoted moving northward. The “Chicago Defender,” which was mostly distributed in the South, claimed that “men, tired of being kicked and cursed, are leaving by the thousands.”

Family members already in the North wrote letters about their lives in there. R.V. Hunt wrote her sister in Memphis about attending musical concerts with whites.

When leaving the South, African Americans often took the train. To save money, they took the shortest and most direct route to the North. Blacks from Middle and West Tennessee mostly ended up in Chicago or Detroit. while those from East Tennessee ended on the east coast in Baltimore or New York City.

Life in the North sometimes was not as great as they had been promised. Working class whites did not want the black migrants in their neighborhoods. They saw them as competition for housing and jobs.

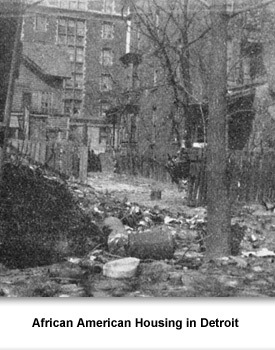

Many migrants ended in segregated neighborhoods, crowded into small, substandard housing. And they dis-cover-ed racial attitudes also existed in the North. One female migrant wrote “I dis-cover-ed that Plainfield (Illinois) was as segregated as the South…You could sit any place on the bus…(but) theaters were segregated, hospitals were segregated, and the churches were.”

Instead of going north, some black leaders promoted the idea of going west to homesteading sites in Kansas and settling there. This was called the “Black Exodus.”

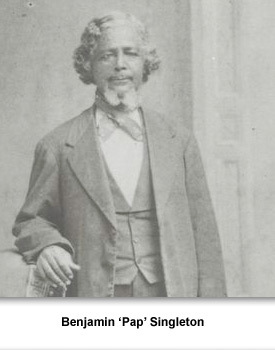

One of the leaders of this movement was Benjamin “Pap” Singleton. He was born a slave in Davidson County, and eventually escaped via the Underground Railroad to Canada. He came back to Nashville after the war ended and worked as a cabinet maker.

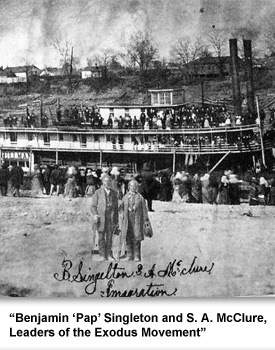

Singleton and a local Nashville preacher, Columbus Johnson, organized a group to promote moving to Kansas. Under the homestead act, anyone who had a $10 filing fee could receive 160 acres of land. If they lived on the property for ten years and made improvements to it, such as building a house or barn, then the land became theirs.

More than 25,000 freed blacks migrated from the South to Kansas during the late 1800s, including more than 5,000 from Nashville alone.Picture Credits:

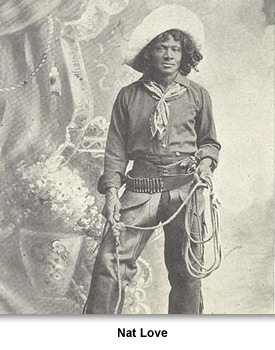

- Photograph of Nat Love. Love was an African American cowboy from Davidson County who moved West. He is shown posing with a rope and other cowboy tools such as a gun and saddle near his feet. This photo was included in his autobiography, Life and Adventures of Nat Love, Better Known in the Cattle Country as Dead Wood Dick published in 1907. University of North Carolina.

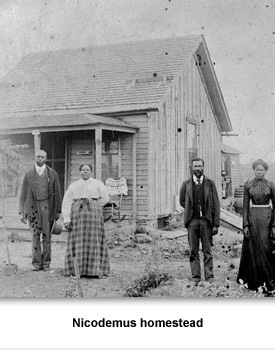

- Photograph showing an early Nicodemus homestead. Nicodemus was an all black town in Kansas founded during the Black Exodus. Library of Congress.

- Photograph of Benjamin ‘Pap’ Singleton. This photo was taken sometime between 1870-1889. Kansas State Historical Society.

- Photograph of “Benjamin ‘Pap’ Singleton and S. A. McClure, Leaders of the Exodus Movement.” This photo was taken in 1876. The two are shown standing in front of a ship that is about to leave Nashville. Kansas State Historical Society.

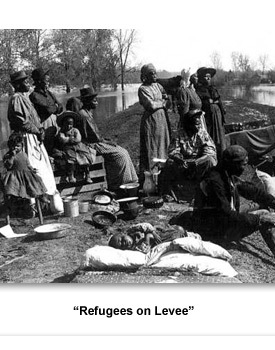

- Photograph entitled, Refugees on Levee. This photo was taken in 1897 and shows a group of African American men, women, and children camped out near a levee on the Mississippi River. Library of Congress.

- Photograph entitled, “A Bull-Gang of riveters.” This photo was created in the 1910s. It shows African American riveters driving with air pressure, while a young boy assists underneath the table. Another young African American boy is also shown working while a white man watches. New York Public Library.

- Photograph of African American housing in Detroit. This photo was published in 1929. New York Public Library.

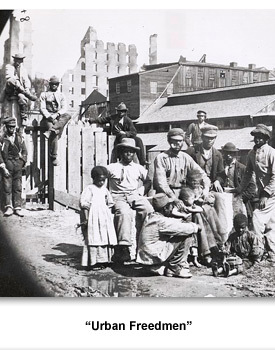

- Photograph entitled, “Urban Freedmen.” This photo was taken sometime during 1863 and 1899. It features a group of African American men and boys posed with several small children. Other African American men can be seen in the background. New York Public Library.

Confronting the Modern Era >> Racial Segregation >> Living with Segregation >> Leaving

Sponsored by: National Endowment for the Humanities

Sponsored by: National Endowment for the Humanities