Stones River

After Shiloh, the Confederate and Union armies chased each other south and north and fought in the Battle of Perryville in Kentucky.

By November 1862, the Confederates now commanded by General Braxton Bragg camped at Murfreesboro while the Union army led by General William S. Rosecrans gathered a large force at Nashville.

The nature of the Civil War was changing. In September 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation set to go into effect on January 1, 1863. This proclamation freed slaves in territory controlled by the Confederacy and for the first time during the war, allowed African American men to serve as Union combat soldiers.

The Union armies suffered several defeats during the fall and winter of 1862 such as the loss at Fredericksburg. Many people in the North feared the Union would lose the war and worried about how the end of slavery would change American society. President Lincoln and the northern people needed a victory.

After receiving considerable pressure from his superiors in Washington to attack the Confederates, Rosecrans finally decided to move late on Christmas night. On December 26, the Union army began its march to Murfreesboro. By nightfall on December 30, the armies faced each other and waited for the battle to come.

The Confederate and Union armies clashed in once peaceful fields near Murfreesboro during the Battle of Stones River (also called the Battle of Murfreesboro) from December 31, 1862, to January 2, 1863.

Dig Deeper: Why do some Civil War battles have different names?

On the first day, the Confederates launched a successful surprise attack. Frightened Union troops, some still preparing their breakfasts, were forced to flee.

As they progressed, Confederate troops encountered increasing resistance. Some federals fought through dense cedar woods until their ammunition was gone. The Confederates almost succeeded in taking the strategic Murfreesboro, Nashville, and Shelbyville Pike and the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad. Union troops in the crucial Round Forest area managed to repel repeated Confederate assaults during the afternoon and save the Union Army from total defeat.

On January 1, the battered armies rested, skirmished, and repositioned their lines. Significantly, Union troops took possession of a hill overlooking McFadden’s Ford (a place where water was shallow enough for people to cross) on the Stones River. Then, on January 2, Bragg ordered his troops to lead a doomed attack against the Union position at McFadden’s Ford.

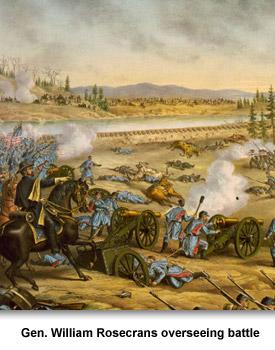

The Confederates successfully pushed Union soldiers back across the river and then charged after the retreating federals. The Confederates did not realize that Union Captain John Mendenhall had placed 58 cannons on the hill directly in their path. The batteries opened on the Confederates, destroying their ranks and effectively ending the battle.

On the next day, Confederates decided to retreat south to Tullahoma, Tennessee, leaving the Union army to claim victory. One-third of the approximately 81,000 soldiers on the field became casualties (wounded, killed, captured or missing in action).

John McCline was 13 years old when he ran away from slavery at the Clover Bottoms plantation near Nashville and joined the Union army as a muleteer, or wagon driver. The army was actually on its way to Stones River when McCline joined its ranks. He arrived with the wagon train in the area where much of the fighting occurred on December 31, 1862. McCline recalled:

The sun was setting, and it was very cold. I had seen very few dead men in my lifetime and, naturally was afraid of them. Of all the horrors that ever greeted a boy’s eyes, here were the worst of them. Thousands of soldiers, killed where they stood…and here they lay in heaps, ready for burial. They were fine specimens of manhood, shot in every conceivable manner—hands, arms, and legs blown off; and where the blood had oozed from their wounds, it had frozen. There was no mistaking the fact—this was real war….

For more information, go to the Stones River National Battlefield website.

Picture Credits:

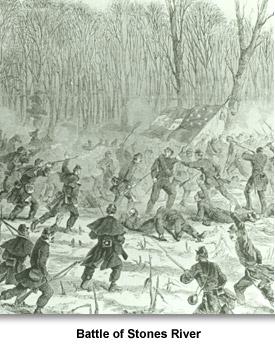

- Battle of Stones River scene from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly newspaper.

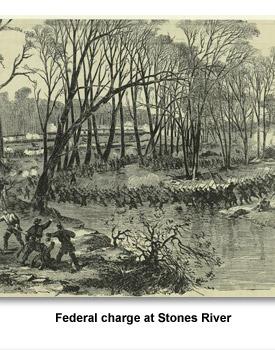

- Print of scene from the Battle of Stones River, “The Decisive Charge of the Federal Troops Across the River.” New York Public Library Digital Collection

- Color print of the Battle of Stones River showing Union Gen. William Rosecrans on a horse (left side) overseeing the battle line. Printed in 1891 by Kurz & Allison, Art Publishers, Chicago, Ill. Library of Congress

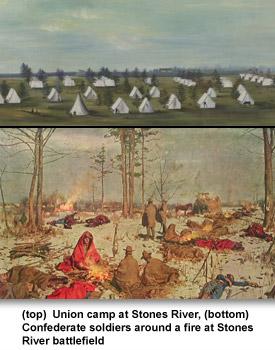

- Painting entitled “Camp of the 64th Ohio Volunteer Infantry on the Battlefield of Stones River, March 27, 1863.” This is after the battle which took place Dec. 31, 1862 to January 2, 1863. Artist is unknown. Tennessee State Museum (TSM) Collection, 88.145.3

- Print of a painting, “Waiting for Dawn,” by Gilbert Gaul. It was copyrighted in 1907 by the Southern Art Publishing Company. The Confederate soldiers are sleeping or sitting around a campfire with dead Union soldiers and horses around them. TSM Collection, 2005.162.3

-

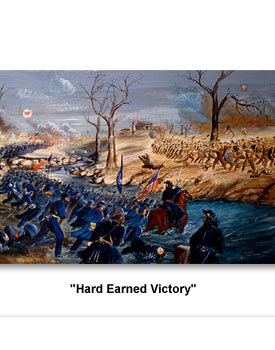

Part of a recreated panorama painting by William D.T. Travis entitled "Hard Earned Victory." The panorama was commissioned shortly after the Civil War ended by veterans of the Army of the Cumberland to memorialize Union General William Rosecrans. This section shows the fighting at Stones River going back and forth across the river. National Museum of American History, Smithsonian

Civil War and Reconstruction >> Civil War >> Battles >> Stones River

Sponsored by: National Endowment for the Humanities

Sponsored by: National Endowment for the Humanities